“Bridge of Spies” vividly recaptures a now-forgotten time in American history.

It was the time of “the Cold War.” A time when:

- America was almost universally seen as “The Good Guy,” in contrast to “The Bad Guy” of the Soviet Union;

- The United States and the Soviet Union held each other at bay with arsenals of nuclear weapons;

- Wisconsin Senator Joseph R. McCarthy terrorized the nation, accusing anyone who disagreed with him of being a Communist–and leaving ruined lives in his wake;

- American TVs blared commercials warning that Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev had boasted: “We will bury you”; and

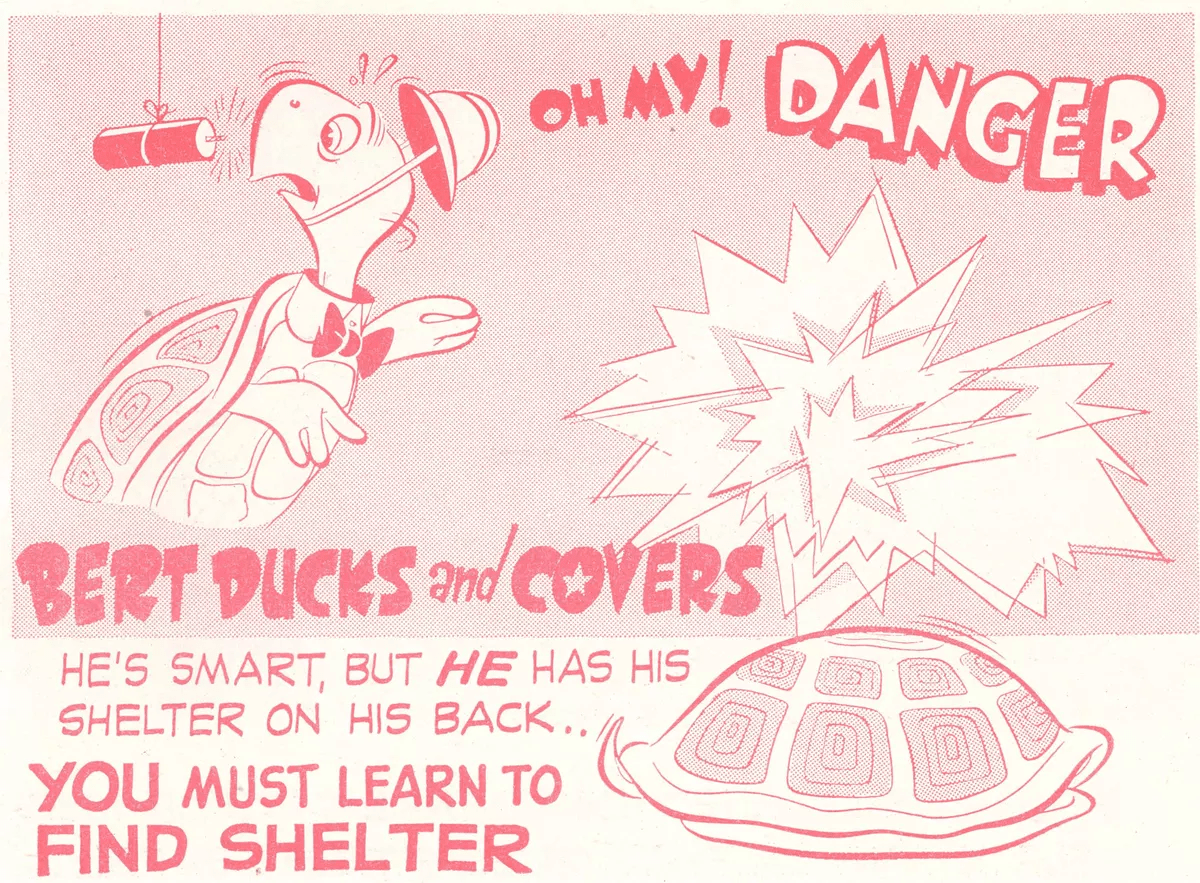

- Children and teenagers were taught in school that they could survive a nuclear attack through “duck and cover” drills. They were instructed to keep their bathtubs filled with water for safe drinking, in the event of a Soviet nuclear strike.

Bert the Turtle teaches schoolchildren to “Duck and Cover”

Yet even in this poisonous atmosphere of fear and denunciation, some men stood out as heroes–simply by holding fast to their consciences.

One of these was a New York insurance attorney named James B. Donovan (played by Tom Hanks). Asked by the Justice Department to defend arrested Soviet spy Rudolph Abel (Mark Rylance) Donovan did what no one expected.

He gave Abel a truly vigorous defense, arguing that the evidence used to convict him was the legally-tainted product of an invalid search warrant.

Upon Abel’s conviction and sentencing to 45 years’ imprisonment, Donovan again shocked the political and legal communities by appealing the case to the Supreme Court.

Donovan argued that Constitutional protections should apply to everyone–including non-Americans–tried in American courts. To do less made a mockery of the very freedoms we claimed to champion.

He lost by a vote of 5-4. But the arguments he made would resurface 50 years later when al-Qaeda suspects were hauled into American courts.

James B. Donovan

In 1961, Donovan was again called upon to render service by a Federal agency–this time the CIA. It wanted his help in negotiating the release of its spy, Francis Gary Powers, shot down over the Soviet Union in 1960 while flying a high-altitude U-2 spy plane.

Throughout “Bridge of Spies,” audiences learn some unsettling truths about how the American government–and governments generally–actually operate.

The first three of these were outlined in Part one of this series:

Truth #1: Appearance counts for more than reality.

Truth #2: Individual conscience can wreck the best-laid plans of government.

Truth #3: High-ranking government officials will ask citizens to take risks they themselves refuse to take.

Now for the remaining truths revealed in this movie.

Truth #4: Appeals to fear often prevail when appeals to humanity are ignored.

After crossing into East Germany, Donovan enters into negotiations with Wolfgang Vogel, a lawyer representing the East German government.

Vogel offers to exchange Frederic Pryor, an American economics graduate student seized by the East German secret police, for Abel. Donovan replies this is a deal-breaker; the United States (which is never mentioned during the negotiations) wants Powers, not Pryor.

Nevertheless, Donovan is equally concerned for Pryor, and adds him to the list of hostages to be released in return for Abel.

Then a new complication arises: The East German government that holds Pryor threatens to pull out. claiming to be insulted because Donovan did not inform them that the USSR was a party to the negotiation.

His reasoned, legal arguments having failed, Donovan resorts to a threat. He conveys a warning to the president of East Germany:

Abel has not yet revealed any Soviet secrets. But if this deal fails, he may well do so to earn favors from the United States government. And, in that case, the Soviets will blame you–Erich Honecker, the president of East Germany–for the resulting damage.

Where arguments based on humanity have failed, this one–based on fear–works. A prisoner-exchange is arranged.

Truth #5: Personal loyalty can supersede bureaucratic inventions.

On February 10, 1962, Donovan, Abel and several CIA agents arrive at the Glienicke Bridge, which connects East and West Germany. The Soviets have Powers, but not Pryor–who is to be released at Checkpoint Charlie, a crossing point between East and West Berlin.

Glienicke Bridge, the “Bridge of Spies”

The CIA agent in charge of the American delegation tells Abel he can cross into East Germany, even though Pryor has not been released.

But Abel has learned that Donovan has negotiated the release of not only Powers but Pryor. Out of loyalty to the man who has vigorously defended him, he waits on his side of the bridge until word arrives that Pryor has been released.

Then Abel crosses into East Germany while Powers crosses into the Western sector.

Donovan returns home. Before flying off to West Germany, he had told his wife he was going on a fishing trip in Scotland.

His wife and children learn the truth about the risks he ran and the success he attained only when a television newscast breaks the news:

Francis Gary Powers has been returned to the United States. And the man responsible is James Donovan, once the most reviled man in America for having defended a notorious Soviet spy.

ABC NEWS, BILL MAULDIN, CBS NEWS, CNN, DONALD TRUMP, FACEBOOK, GENERAL LUCIAN K. TRUSCOTT, GEORGE W. BUSH, IRAQ WAR, JEB BUSH, MEMORIAL DAY, NATIONAL CONSERVATIVE POLITICAL ACTION CONFERENCE (CPAC), NBC NEWS, OLD GLORY, SADDAM HUSSEIN, SAVING PRIVATE RYAN, SCOTT WALKER, STEVEN SPIELBERG, THE CHICAGO SUN-TIMES, THE CHICAGO TRIBUNE, THE LOS ANGELES TIMES, THE NEW YORK TIMES, THE WASHINGTON POST, TWITTER, WEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTION, WHITE HOUSE CORRESPONDENTS DINNER, WORLD WAR ii

A FADING GLORY

In Bureaucracy, History, MSNBC, Politics, Social commentary, Uncategorized on February 2, 2016 at 12:01 amDonald Trump has repeatedly boasted that, if elected President, he will “make America great again.”

He would do well to re-watch Saving Private Ryan, Steven Spielberg’s 1998 World War II epic.

This opens with a scene of an American flag snapping in the wind. Except that the brilliant colors of Old Glory have been washed out, leaving only black-and-white stripes and black stars.

And then the movie opens–not during World war II but the present day.

Did Spielberg know something that his audience could only sense? Such as that the united States, for all its military power, has become a pale shadow of its former glory?

May 30, 1945, marked the first Memorial Day after World War II ended in Europe. On that day, the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery, near the town of Nettuno, held about 20,000 graves.

Most were soldiers who died in Sicily, at Salerno, or at Anzio. One of the speakers at the ceremony was Lieutenant General Lucian K. Truscott, Jr., the U.S. Fifth Army Commander.

Lieutenant General Lucian K. Truscott, Jr.

Unlike many other generals, Truscott had shared in the dangers of combat, pouring over maps on the hood of his jeep with company commanders as bullets or shells whizzed about him.

When it came his turn to speak, Truscott moved to the podium. Then he turned his back on the assembled visitors–which included several Congressmen.

The audience he now faced were the graves of his fellow soldiers.

Among those who heard Truscott’s speech was Bill Mauldin, the famous cartoonist for the Army newspaper, Stars and Stripes. Mauldin had created Willie and Joe, the unshaved, slovenly-looking “dogfaces” who came to symbolize the GI.

Bill Mauldin and “Willie and Joe,” the characters he made famous

It’s from Mauldin that we have the fullest account of Truscott’s speech that day.

“He apologized to the dead men for their presence there. He said that everybody tells leaders that it is not their fault that men get killed in war, but that every leader knows in his heart that this is not altogether true.

“He said he hoped anybody here through any mistake of his would forgive him, but he realized that he was asking a hell of a lot under the circumstances….

“Truscott said he would not speak of the ‘glorious’ dead because he didn’t see much glory in getting killed in your teens or early twenties.

“He promised that if in the future he ran into anybody, especially old men, who thought death in battle was glorious, he would straighten them out. He said he thought it was the least he could do.

“It was the most moving gesture I ever saw,” wrote Mauldin.

Then Truscott walked away, without acknowledging his audience of celebrities.

Fast forward 61 years later–to March 24, 2004.

At a White House Correspondents dinner in Washington, D.C., President George W. Bush joked publicly about the absence of Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMDs) in Iraq.

One year earlier, he had ordered the invasion of Iraq on the premise that its dictator, Saddam Hussein, possessed WMDs he intended to use against the United States.

To Bush, the non-existent WMDs were nothing more than the butt of a joke that night. While an overhead projector displayed photos of a puzzled-looking Bush searching around the Oval Office, Bush recited a comedy routine.

“Those Weapons of Mass Destruction have gotta be here somewhere,” Bush laughed, while a photo showed him poking around the corners of the Oval Office.

“Nope–no weapons over there! Maybe there’s under here,” he said, as a photo showed him looking under a desk.

In a scene that could have occurred under the Roman emperor Nero, an assembly of wealthy, pampered men and women–the elite of America’s media and political classes–laughed heartily during Bush’s performance.

Only later did the criticism come, from Democrats and Iraqi war veterans–especially those veterans who had lost comrades or suffered horrific wounds to protect America from a threat that had never existed.

Then fast forward another 11 years–to February 27, 2015.

The Republican party’s leading Presidential contenders for 2016 gathered at the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) in National Harbor, Maryland.

Although each candidate tried to stake his own claim to the Oval Office, all of them agreed on two points:

First, President Barack Obama had been dangerously timid in his conduct of foreign policy; and

Second, they would pursue aggressive military action in the Middle East.

“Our position needs to be to re-engage with a strong military and a strong presence,” said Jeb Bush, the former governor of Florida. And Bush added that he would consider sending ground forces to fight ISIS.

Scott Walker, the current governor of Florida, equated opposing labor unions to fighting terrorists: “If I could take on 100,000 protesters (in Wisconsin) I can do the same across the world.”

Neither Bush nor Walker had seen fit to enter the ranks of the military he wished to plunge into further combat. And Bush and Walker are typical of those who make up the United States Congress:

Of those members elected or re-elected to the House and Senate in November, 2014, only 97–less than 18%–have served in the U.S. military.

Small wonder then, that, for many people, Old Glory has taken on a darker, washed-out appearance, in real-life as in film.

Share this: