On August 17, Republican Presidential candidate Donald Trump outlined his strategy for defeating the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS).

He would order American forces to take over the oil fields that ISIS has seized in Iraq.

Trump outlined his plans for future military operations against ISIS on NBC’s “Meet the Press” with Chuck Todd.

Trump said he never advocated a U.S. war with Iraq, but it happened, and “it was a big mistake” because it “destabilized” the Middle East.

“Now we’re there, and you have ISIS….And ISIS is taking over a lot of the oil in certain areas of Iraq.

“And I said, you take away their wealth. You go and knock the hell out of the oil. Take back the oil. We take over the oil, which we should have done in the first place.”

After taking over the Iraqi oil fields, said Trump, “we’re going to have so much money.

“And what I would do with the money that we make, which would be tremendous, I would take care of the soldiers that were killed, the families of the soldiers that were killed, the soldiers, the wounded warriors that are–see, I love them.”

Actually, Trump’s idea forms the plot of The Profession, a 2011 novel by bestselling author Steven Pressfield.

Pressfield made his literary reputation with a series of classic novels about ancient Greece.

In Gates of Fire (1998) he explored the rigors and heroism of Spartan society–and the famous last stand of its 300 picked warriors at Thermopylae.

In The Virtues of War (2004) he entered the mind of Alexander the Great, whose armies swept across the known world, destroying all who dared oppose them.

Finally, in The Afghan Campaign (2006) Pressfield–this time from the viewpoint of a lowly Greek soldier–refought Alexander’s brutal, three-year anti-guerrilla campaign in Afghanistan.

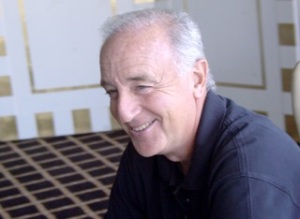

Steven Pressfield

But in The Profession, Pressfield created a plausible world set into the future of 2032. The book’s own dust jacket offers the best summary of its plot-line:

“The third Iran-Iraq war is over. The 11/11 dirty bomb attack on the port of Long Beach, California is receding into memory. Saudi Arabia has recently quelled a coup. Russians and Turks are clashing in the Caspian Basin….

“Everywhere military force is for hire. Oil companies, multi-national corporations and banks employ powerful, cutting-edge mercenary armies to control global chaos and protect their riches.

“Even nation states enlist mercenary forces to suppress internal insurrections, hunt terrorists, and do the black bag jobs necessary to maintain the new New World Order.

“Force Insertion is the world’s merc monopoly. Its leader is the disgraced former United States Marine General James Salter, stripped of his command by the president for nuclear saber-rattling with the Chinese and banished to the Far East.’

Salter appears as a hybrid of World War II General Douglas MacArthur and Iraqi War General Stanley McCrystal.

Like MacArthur, Salter has butted heads with his President–and paid dearly for it. Now his ambition is no less than to become President himself–by popular acclaim. And like McCrystal, he is a pure warrior who leads from the front and is revered by his men.

Salter seizes Saudi oil fields, then offers them as a gift to America. By doing so, he makes himself the most popular man in the country–and a guaranteed occupant of the White House.

And in 2032 the United States is a far different nation from the one its Founding Fathers created in 1776.

“Any time that you have the rise of mercenaries…society has entered a twilight era, a time past the zenith of its arc,” says Salter.

“The United States is an empire…but the American people lack the imperial temperament. We’re not legionaries, we’re mechanics. In the end the American Dream boils down to what? ‘I’m getting mine and the hell with you.’”

Americans, asserts Salter, have come to like mercenaries: “They’ve had enough of sacrificing their sons and daughters in the name of some illusory world order. They want someone else’s sons and daughters to bear the burden….

“They want their problems to go away. They want me to to make them go away.”

And so Salter will “accept whatever crown, of paper or gold, that my country wants to press upon me.”

More than 500 years ago, Niccolo Machiavelli warned of the dangers of relying on mercenaries:

“Mercenaries…are useless and dangerous. And if a prince holds on to his state by means of mercenary armies, he will never be stable or secure; for they are disunited, ambitious, without discipline, disloyal; they are brave among friends; among enemies they are cowards.

Niccolo Machiavelli

“They have neither the fear of God nor fidelity to men, and destruction is deferred only so long as the attack is. For in peace one is robbed by them, and in war by the enemy.”

Centuries ago, Niccolo Machiavelli issued a warning against relying on men whose first love is their own enrichment.

Steven Pressfield, in a work of fiction, has given us a nightmarish vision of a not-so-distant America where “Name your price” has become the byward for an age.

Both warnings are well worth heeding.

"EXCALIBUR", ABC NEWS, AFGHANISTAN, ALEXANDER THE GREAT, CBS NEWS, CNN, GEORGE W. BUSH, IRAQ, JOHN BOORMAN, KING ARTHUR, MSNBC, NBC NEWS, STEVEN PRESSFIELD, THE AFGHAN CAMPAIGN, THE CHICAGO SUN-TIMES, THE CHICAGO TRIBUNE, THE HUFFINGTON POST, THE LOS ANGELES TIMES, THE NEW YORK TIMES, THE VIRTUES OF WAR, THE WASHINGTON POST, U.S. MARINE CORPS

SOLDIERING IN AFGHANISTAN: THEN AND NOW

In History, Military, Politics, Social commentary on December 25, 2015 at 3:26 pmIn “Excalibur,” director John Boorman’s brilliant 1981 telling of the King Arthur legends, Merlin warns Arthur’s knights–and us: “For it is the doom of men that they forget.”

Not so Steven Pressfield, who repeatedly holds up the past as a mirror to our present. Case in point: His 2006 novel, The Afghan Campaign.

By 2006, Americans had been fighting in Afghanistan for five years. And today, almost ten years into the same war, there remains no clear end in sight–to our victory or withdrawal.

Pressfield’s novel, although set 2,000 years into the past, has much to teach us about what are soldiers are facing today in that same alien, unforgiving land.

Matthias, a young Greek seeking glory and opportunity, joins the army of Alexander the Great. But the Persian Empire has fallen, and the days of conventional, set-piece battles–where you can easily tell friend from foe–are over.

Alexander next plans to conquer India, but first he must pacify its gateway–Afghanistan. Here that the Macedonians meet a new–and deadly–kind of enemy.

“Here the foe does not meet us in pitched battle,” warns Alexander. “Even when we defeat him, he will no accept our dominion. He comes back again and again. He hates us with a passion whose depth is exceeded only by his patience and his capacity for suffering.”

Alexander the Great

Matthias learns this early. In his first raid on an Afghan village, he’s ordered to execute a helpless prisoner. When he hesitates, he’s brutalized until he strikes out with his sword–and botches the job.

But, soon, exposed to an unending series of atrocities–committed by himself and his comrades, as well as the enemy–he finds himself transformed.

And he hates it. He agonizes over the gap between the ideals he embraced when he became a soldier–and the brutalities that have drained him of everything but a grim determination to survive at any cost.

Pressfield, a former Marine himself, repeatedly contrasts how civilians see war as a kind of “glorious” child’s-play with how soldiers actually experience it.

Steven Pressfield

He creates an extraordinary exchange between Costas, an ancient-world version of a CNN war correspondent, and Lucas, a soldier whose morality is outraged at how Costas and his ilk routinely prettify the indescribable.

And we know the truth of this exchange immediately. For we know there are doubtless brutalities inflicted by our troops on the enemy–and atrocities inflicted by the enemy upon them–that never make the headlines, let alone the TV cameras.

We also know that, decades from now, thousands of our former soldiers will carry horrific memories to their graves. These memories will remain sealed from public view, allowing their fellow but unblooded Americans to sleep peacefully, unaware of the terrible price that others have paid on their behalf.

Like the Macedonians (who call themselves “Macks”), our own soldiers find themselves serving in an all-but-forgotten land among a populace whose values could not be more alien from our own if they came from Mars.

Instincitvely, they turn to one another–not only for physical security but to preserve their last vestiges of humanity. As the war-weary veteran, Lucas, advises:

“Never tell anyone except your mates. Only you don’t need to tell them. They know. They know you. Better than a man knows his wife, better than he knows himself. They’re bound to you and you to them, like wolves in a pack. It’s not you and them. You are them. The unit is indivisible. One dies, we all die.”

Put conversely: One lives, we all live.

Pressfield has reached into the past to reveal fundamental truths about the present that most of us could probably not accept if contained in a modern-day memoir.

These truths take on an immediate poignancy owing to our own current war in Afghanistan. But they will remain just as relevant decades from now, when our now-young soldiers are old and retired.

This book has been described as a sequel to Pressfield’s The Virtues of War: A Novel of Alexander the Great, which appeared in 2004. But it isn’t.

Virtues showcased the brilliant and luminous (if increasingly dark and explosive) personality of Alexander the Great, whose Bush-like, good-vs.-evil rhetoric inspired men to hurl themselves into countless battles on his behalf.

But Afghan thrusts us directly into the flesh-and-blood realities created by that rhetoric: The horrors of men traumatized by an often unseen but always menacing enemy, and the horrors they must inflict in return if they are to survive in a hostile and alien world.

Share this: